Hubble’s Heir: The James Webb Space Telescope

JWST Full-scale model. Credit: EADS Atrium

Nobel Prize Winner John Mather speaks about the challenges of building the James Webb Space Telescope. It will be the heir to the Hubble Space Telescope.

September 10, 2023 No Comments

Does every black hole harbour another universe?

What if at the centre of every black hole exists another universe?

Could the event horizon of a black hole be the bridge to another universe?

What about the singularity that’s supposed to exist inside each black hole?

In this New Scientist story, I write about a controversial idea — based on a modification to Einstein’s equations of general relativity that use an extra geometric property of spacetime called torsion — that matter doesn’t get crushed to infinite density inside a black hole. Instead, torsion becomes a dominant property at extremely high densities and serves to repulse gravity, causing matter and spacetime to rebound. The researcher suggests that this could lead to an expanding universe inside a black hole.

What is intriguing is that this rebounding spacetime inside a black hole could create conditions that solve the horizon and flatness problems of the big bang theory. Take the flatness problem. The universe today is flat, but in order for it to be so, the curvature of spacetime would have had to be fine-tuned to ridiculous precision at the big bang, otherwise spacetime would not be flat today. Inflationary theory — the idea that our universe underwent an episode of exponential expansion just after the big bang — was devised to take care of the flatness problem.

The universe-inside-a-black-hole idea does away with the need for inflation.

What does this mean? Is there an infinite recursion of black holes inside universes inside black holes inside universes …

Hmmm…

July 26, 2023 1 Comment

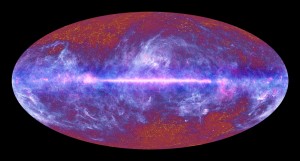

PLANCK paints first all-sky CMB map

The European Space Agency has announced that its Planck satellite has completed its first all-sky survey of the universe.

The image shows the radiation from the dust in our galaxy in blue, the white hot gas is in the centre, and the mottled backdrop is the cosmic microwave background. Click here for a high-res image.

The foreground of the emissions from the galactic dust and gas will have to be subtracted to obtain the clear map of the cosmic microwave background, which is the radiation left over from the big bang, a light that is about 13.4 billion years old!

It’s Planck’s ability to gather high resolution information about the foreground emissions that will allow it to map the CMB as never before, better than NASA’s still-orbiting WMAP satellite or any other instruments that came before.

This survey took 10 months, starting in August 2009. By the time the mission ends in 2012, Planck hopes to have studied the entire sky four times over.

July 5, 2023 No Comments

Neutrinos continue to astound

It’s only been a couple of weeks since we heard of the OPERA experiment detecting the first-ever oscillation of a muon neutrino into a tau neutrino. Now, the MINOS experiment at FERMILAB has announced that they have seen a difference in the way neutrinos and anti-neutrinos oscillate (see story in New Scientist).

Here’s what’s happening in the experiment. A source of neutrinos and anti-neutrinos at FERMILAB is beaming these particles towards two detectors. One is the “near” detector, close to the source. The other is 700 km away, inside an abandoned iron mine in Soudan, Minnesota (which is also the site of the CDMS-II experiment, which is looking for dark matter. For pictures of trip to mine, see here.).

According to our best understanding of neutrino physics, both neutrinos and anti-neutrinos should oscillate in a similar manner: meaning, they should change from muon neutrinos to tau neutrinos and from muon anti-neutrinos to tau anti-neutrinos in much the same fashion.

As it happens, the MINOS detector in Soudan is seeing a difference in the way neutrinos and their anti-matter counterparts are oscillating.

If this result is substantianted by further data or by other experiments, it could be a big breakthrough. Somewhere in this lie clues to explain the matter-antimatter asymmetry in our universe. What happened to all the antimatter that must have been produced in the early universe?

It’s possible that the discrepancy in how neutrinos and anti-neutrinos oscillate, or the difference in the way they interact with 700 km of Earth on their way from FERMILAB to the Soudan mine, could enlighten us about new physics, and shed more light on the mystery of the missing antimatter.

June 17, 2023 1 Comment

OPERA tunes into first-ever tau neutrinos

The OPERA experiment in the underground Gran Sasso Laboratory in Italy has likely seen the first tau neutrino, making it the first time that a neutrino type may have been seen “appearing” rather than “disappearing”.

Before we dig further into this strange statement and why it’s important, here’s a bit of background on neutrino appearances and disappearances. Neutrinos come in three flavours: electron, muon and tau. During the 1960s, neutrino detectors showed that there was a deficit of neutrinos coming from the sun. This came to be called the mystery of the missing solar neutrinos. Eventually, physicists figured out that the neutrinos were morphing from one type to another on their journey from the sun to the Earth. So if a detector was sensitive to only one type of neutrino, then it would see less of that type than was being emitted by the sun, since that particular neutrino type had changed into another type along the way, and hence could not be seen by the detector. This phenomenon is called neutrino oscillation.

This “disappearance” of a neutrino type has been detected by various detectors worldwide.

But how about detecting the reverse process? Say a neutrino source is spewing out muon neutrinos, and some of them are changing to tau neutrinos on their way to the detector. How about detecting the “appearance” of the neutrino which was not produced at the source?

That’s exactly what OPERA has done. A neutrino source at the CERN Accelerator Complex has been generating muon neutrinos. These neutrinos travel 730 kilometres to the OPERA detector (in about 2.4 milliseconds). Now, OPERA has most likely found one tau neutrino from among the many billions of muon neutrinos produced at CERN. This tau neutrino “appeared”—it is of course equivalent to a muon neutrino disappearing. But still, it’s a first.

Why is all this important? It turns out that neutrino oscillations require neutrinos to have mass, something which is not allowed in the standard model of particle physics. New physics is required to explain the process, and the more we study neutrino oscillations, the clearer the new physics will become.

Hitoshi Murayama, a theoretical physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote about the announcement of the discovery of neutrino oscillations in Japan in 1998 (quoted in The Edge of Physics): “It was a moving moment. Uncharacteristically for a physics conference, people gave the speaker a standing ovation. I stood up too. Having survived every experimental challenge since the late 1970s, the Standard Model had finally fallen. The results showed that at the very least the theory is incomplete.”

May 31, 2023 3 Comments

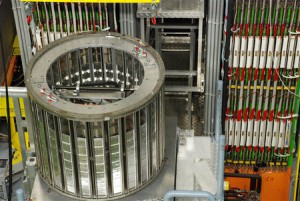

LHC steps up on the bunches

According to the US LHC team’s twitter feed, the Large Hadron Collider is now running with 13 bunches of protons per beam. That’s a significant step up from the single bunch of protons per beam that the LHC began operations.

Each bunch of protons is moving around the 27-kilometre-long tunnel at near the speed of light, completing 11,245 trips round the ring every second. There is one beam moving clockwise, and another counterclockwise. At four points along the ring, these beams cross and the protons bunches collide.

Each time two bunches cross paths, about 200 billion protons are involved. However, only about 20 protons actually collide, the rest just continue unimpeded. When the LHC will be running at full-tilt, with about 2808 bunches in each beam, then even though just 20 of the 200 billion protons collide, the sheer number of bunches crossing per second means that about 100 billion particles per second will be produced at each of the four collision points of the LHC.

That’s where detectors like ATLAS and CMS will be monitoring particle tracks, hoping to find the Higgs, dark matter particles, signs of supersymmetry or even extra dimensions.

Stay tuned.

May 25, 2023 1 Comment

New supernova might undermine dark matter search

THE DISCOVERY OF A NEW TYPE OF supernova, reported in this week’s Nature, could have implications for indirect detection of dark matter.

This supernova, SN2005E, spewed out calcium and titanium. The calcium, of course, is the stuff of our bones, showing even more emphatically — not that there was ever any doubt — that we are all “made of star stuff”, as Carl Sagan poetically put it.

The titanium is far more interesting. It’s radioactive, and emits positrons as it decays. Over the past couple of years, balloon and satellite-based experiments, such as ATIC and PAMELA, have reported seeing an excess of positrons coming from outer space. This excess has been attributed to the anniliation of dark matter particles, though, theorists have struggled to reconcile the various results. The only serious contender for a source of positrons are pulsars, and we don’t know enough about the distribution of pulsars to rule them out or in.

Now, astronomers are saying that this new class of supernova could be quite common, and if the titanium ejected from them is putting out positrons, it could account for the excess being seen by experiments.

Where does that leave the claims of dark matter detection? In a spot of bother. Of course, this doesn’t mean that dark matter doesn’t exist, but it does pose uncomfortable questions about the claims of the past years.

May 20, 2023 No Comments

The gorgeous Southern Pinwheel Galaxy

image courtesy ESO

The European Southern Observatory released a gorgeous image of the Southern Pinwheel galaxy, or Messier 83. At about 40,000 light years across, it’s about 2.5 times smaller than the Milky Way, but apart from the smaller size, it’s a good proxy for what our own galaxy might look like.

The picture was taken by the Wide Field Imager (WFI) attached to a 2.2-metre telescope at La Silla, in the Chilean Andes.

May 19, 2023 1 Comment

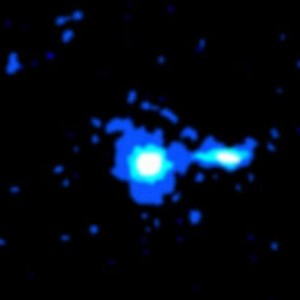

Mystery quasar alignment due to cosmic strings?

A mysterious alignment of quasars in the distant universe, found in a survey by Damien Hutsemeker of the University of Liege, Belgium, and his colleagues, has confounded cosmologists.

Why should the quasars, which should have random orientations in space, show such an alignment.

A New Scientist article argues that cosmic strings (which are kinks in spacetime, not the strings of string theory) that formed in the early universe could be responsible.

The quasars have also been liked to the “Axis of Evil” - another seemingly non-random alignment of cold and hot spots in the cosmic microwave background.

Regardless of what the explanation is, this is a great example of the convergence of astronomy, cosmology and particle physics (in this case, the cosmic strings invoked in the above article are predicted by the standard model of particle physics).

May 7, 2023 1 Comment

NASA’s Balloon Crash – Don’t forget the successes

On 29 April, one of NASA’s Long Duration Balloon flights failed even before it could get lift-off, smashing the two-tonne Nuclear Compton Telescope (NCT) into the ground and into a car, before stumbling to a stop. This happened in Australia.

The event got plenty of media attention, highlighting our hunger for disaster stories.

But what of all the successes of NASA’s Long Duration Balloon flights? Since the 1960s, NASA has launched more than 2000 flights, and only about 4 per cent have failed. We rarely hear of the incredible work that goes into launching one of these balloons when everything goes well. Especially the efforts that go into getting the balloons and payloads off the ground (or ice) in Antarctica. For instance, when the BOOMERANG experiment flew over Antarctica in the austral summer of 1998-99 and returned with precision measurements of the cosmic microwave background, it made headline news. But it was the experiment that made news, not the balloon launch.

In the summer of 2007-08, I witnessed three such launches from the Ross Ice Shelf near McMurdo, Antarctica. So, to give where credit is due, here’s a description from The Edge of Physics of just what it takes to get these behemoths off the ground (plus there’s a video at the end):

The moment the weatherman gave the word, the heavy-vehicle crew swung into action. All the equipment—which had been brought by cargo ship to McMurdo after icebreakers had cleared the way—had to be assembled for launch. A Caterpillar tractor crunched toward the launch pad, hauling a box with a neatly folded balloon. Two other tractors each pulled trailers loaded with twelve giant tanks of helium. The launch vehicle was already on the ice, parked nearly at the center of the circular launch pad, its boom aligned to the predicted direction of launch-time winds. The payload hung from the boom. The crew connected the payload to the parachute and set it down behind the launch vehicle. At this point, they could still be called back if the winds changed. But the conditions continued to look good, so the crew started assembling the balloon. A long strip of canvas was laid over the snow between the box containing the balloon and the parachute. Gingerly, the crew pulled out the folded balloon, sheathed in bright red plastic, and set it out on the canvas. Even the immensity of the ice shelf could not dwarf its size, as it stretched from one end of the launch pad, where the helium tanks stood, to the payload and parachute near the center. The work was done with extreme care, for the parachute is made of polyethylene plastic film a mere 0.0008 inches thick—about the thickness of a sandwich bag. Then, the crew cabled the balloon to the parachute and wired up its control electronics, working quickly before the cold rendered their fingers useless.

It was time to inflate the balloon. There was no going back now. A section of the balloon was fed under a large spool, which was mounted on a sled being pulled by a Caterpillar tractor. Two tentacle-like fill tubes coming out of the sides of the balloon were connected to valves, each held by a crew member. The valves were attached to long, thin, black hoses that snaked over the snow to the helium tanks. Everyone was asked to move away, because a broken hose, with pressurized helium flowing, can lash out with enough force to sever a leg.

The helium was released from the tanks, and the fill tubes engorged, looking like transparent billowing beasts that had to be tamed by the crew. The high-pitched whine of the pressurized helium rent the air. The top of the balloon filled up and rose. Dragging the spool sled slowly toward the payload, the crew let more of the balloon through, until all the helium had been injected. The fill tubes were disconnected and tied up tight. Filling the balloon had taken nearly an hour, and canceling the launch now meant the balloon would be lost. The expensive helium, too. Luckily, the winds were fine. I heard Klein, the launch manager, shout, “Release the balloon, release the balloon!” The directive rang out on all hand-held radios around the launch pad. The crew disengaged the spool, which swung quickly aside. The freed balloon rose in slow motion, with a mighty flapping of plastic. The Antarctic cold reduces the volume of a gas. As a result, the balloon didn’t fully inflate. It looked like a giant translucent jellyfish, its tied-up tentacle-like fill tubes rounding out the picture.

In a matter of seconds, the balloon was above the launch vehicle. If the wind is calm, the balloon should hold steady right over the payload, but often that’s not the case. The balloon blows with the wind, however slight, and it can drag the launch vehicle around with it, so the driver has to keep the payload directly beneath the balloon. But the balloon is directly above the vehicle, so for all practical purposes he’s driving blind.

To help out, the crew chief was standing on the launch vehicle, looking up at the balloon and shouting directions into his radio: Left, right, forward, back, slow down, speed up … until the vehicle was moving at just the right speed and direction and the balloon and the payload were vertically lined up. It was time to let the balloon go. The driver braked and reversed direction. The crew pulled a pin that connected the payload to the boom, and the balloon took up the weight of the payload. This is always a tense moment, for even a tiny error can cause the payload to swing like a pendulum and smash into the vehicle or into the ground.

If it goes right, though, it’s transcendent.

The heavy payload hovered above the ground for a moment, then started to soar. Five hundred feet per minute. Everyone on the launch pad cheered, some for joy at having seen something magical, others at the relief of a launch perfectly executed. Then a hush descended as the balloon rose against the backdrop of Mount Erebus. It was still long and thin and far from its final shape. The payload swiveled beneath, its shiny surfaces and solar panels glinting occasionally as they caught the sun. The balloon looked fragile, the payload even more so. For a while, the whole ensemble seemed to slow down, partly because the cloudless blue sky offered no sense of scale, but also because you perceive that something is rising only if it is getting smaller. In this case, the balloon was getting larger by the minute. The helium was expanding as the atmospheric pressure dropped. Everything seemed suspended, allowing us below to catch our breath and marvel.

Within about three hours, the balloon would punch through the troposphere, after experiencing temperatures as low as -49ºF. The helium would expand to more than two hundred times its volume during launch, and the balloon would be fully stretched, resembling a giant diaphanous pumpkin nearly 400 feet across. Against a blue sky, it would be almost 80 percent the size of the full moon. Airline pilots flying below such launches, unable to discern the size of this curious object, have repeatedly been tricked into thinking that the balloon is closer to them than it actually is—at 120,000 feet, however, it’s twice as high above the airplane as the plane is above the ground. Hours later, I could see the balloon from McMurdo Station, as it flew over the Transantarctic Mountains on its long journey around the South Pole.

Here’s a video of the balloon launch in Antarctica (courtesy Ryan Miller and Jessica Reynolds of Polar Palooza):

May 4, 2023 No Comments