Posts from — October 2010

India’s giant neutrino observatory gets the nod

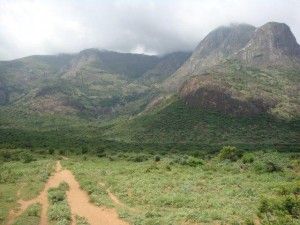

Site for the Indian Neutrino Observatory (credit: M V N Murthy)

THE INDIAN NEUTRINO OBSERVATORY received a big boost last week when the Ministry of Environment and Forests gave it formal approval.

The observatory will host a massive neutrino detector, which will include 50,000 tonnes of magnetised iron, making it the largest of its kind in the world. The largest magnet being used in physics experiments today is in the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector at CERN.

After almost half-a-century, Indian physicists will attempt to get back at the forefront of neutrino physics.

In the 1960s, India hosted one of the world’s first underground neutrino experiments. Called the Kolar Gold Fields neutrino experiment, it was built inside a 2316-metre-deep gold mine in Southern India. In 1965, the experiment became the first to detect atmospheric neutrinos. Here’s a report about the experiment from the CERN website.

Here is my New Scientist story with more details about the Indian Neutrino Observatory.

October 23, 2022 No Comments

Cosmic backlight shows up giant galaxy cluster

THE SOUTH POLE TELESCOPE has discovered the most massive cluster of galaxies yet seen at a distance of 7 billion light years.

The 10-meter SPT is an extremely sensitive radio telescope, designed to study the cosmic microwave background, the universe’s first light that was emitted when the cosmos was about 370,000 years old.

As the CMB travels towards us, it encounters mostly empty space. But occasionally, it’ll have to pass through a galaxy cluster, and this has the effect of reducing the temperautre of the CMB photons. It’s called the Sunayev-Zeldovich effect, after the scientists who predicted it in the 1970s.

It’s these cool spots in the CMB that the SPT is trying to find-and it did find one that led to the discovery of the massive cluster, which has a mass of 800 trillion suns.

What is amazing is that the cosmic microwave background, which is itself an extremely faint radiation, is now being used a cosmic back-light, shining at us from the early universe, before any large-scale structures had formed. Galaxy clusters show up as shadows-in a manner of speaking-against this back-light, helping us see the universe’s earliest giant structures which would be too faint for optical telescopes.

The above picture was taken when the SPT was still under construction (it doesn’t have the ground shield that will protect it from radiation reflected off the snow and ice). During my visit to the South Pole, I thought this telescope was one of the most beautiful I had seen through all my trips to write The Edge of Physics.

See here for press release from the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

October 18, 2023 No Comments

Discoverer of Einstein’s Cross-John Huchra-dies unexpectedly

Celebrated astronomer and Harvard University professor John Huchra died unexpectedly on Friday, 8 October. He was 61.

Huchra is best known for conducting the impressive CfA Redshift Survey, on which he collaborated with astronomer Margaret Geller. The survey, which mapped out the large-scale structure of the universe, found a giant wall of galaxies that spanned across 500 million light years. The universe, they found, is made of giant voids, or bubbles of empty space, with galaxies clustering on the surface of these bubbles.

Huchra also has a very intriguing object named after him: a spectacular object known as Huchra’s Lens, also called Einstein’s Cross (see this link for a high resolution image).

I interviewed Huchra by email for my book The Edge of Physics. Here is an excerpt from the book (slightly edited) describing Huchra’s discovery of the eponymous gravitational lens.

The Einstein Cross is one of the more celebrated examples of gravitational lensing. It, too, was discovered unexpectedly, in 1985, by astronomer John Huchra of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Huchra and colleague Margaret Geller and their team were measuring the velocities of eighteen thousand bright galaxies in the northern sky. The farthest galaxy in their study was about 700 million light-years away. One night, Huchra was observing with a 4.5-meter telescope on Mount Hopkins, about 30 miles south of Tucson, Arizona, when his technician, who was observing with a smaller telescope, called. He had found a galaxy with a spectrum that did not make sense. Huchra observed it with a better instrument and immediately recognized it as a quasar. But there was a problem. Quasars, which are the universe’s brightest objects, are from a very distant past; they lie far beyond the regions that Huchra’s team was studying and shouldn’t have shown up in the observations. Sure enough, when Huchra examined the spectrum and its redshift, he realized that the quasar was nearly 8 billion light-years away. Something very strange was going on.

There was yet another mystery surrounding the unusual object. When Huchra studied the spectrum at the center of the object, he detected a galaxy that was only about 500 million light-years away. Whatever they had found seemed to be a mixture of a nearby galaxy and an astonishingly distant quasar. More observations followed, and the astronomers realized that they were probably staring at a gravitational lens.

It was caused by a phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s general theory of relativity—the bending of light from a distant object by the gravitational field of a massive galaxy in the foreground: five bright blobs, one at the center and the four others positioned at the corners of an imaginary cross. The blobs were actually a quasar, which is a giant galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its center.

October 13, 2023 No Comments

WMAP — RIP

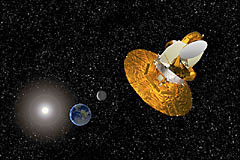

courtesy NASA

AFTER 9 years of staring into space and mapping the cosmic microwave background, WMAP has finally called it a day (or night).

NASA has terminated the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe’s extraordinary mission. The probe, which was orbiting around Lagrangian Point 2 (L2) for all these years, fired its thrusters and entered into permanent orbit around the Sun. L2 is a million miles from Earth, and is a point where the gravitational forces of the Earth and the Sun balance out in a way that any spacecraft in orbit around L2 has to expend very little energy to do so.

WMAP mapped the cosmic microwave background, the radiation that comes to us from when the universe was a mere 370,000 years old, with unprecedented precision.

Some WMAP highlights:

- Was the first spacecraft to operate from Lagrangian Point 2

- Established that the age of the universe is 13.75 billion years

- Established that about 72 per cent of the universe is made of dark energy and 23 per cent of it is made of dark matter

- Provided the first solid support of the idea that the universe expanded exponentially fractions of a second after the big bang, an episode called inflation

The baton has now been handed over to the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite, which is already in orbit around L2, and is continuing to map the CMB with greater precision.

October 6, 2023 No Comments